The cells characterizing healthy metazoa bodies are meant to share and maintain the same genome, with tissue diversity being originated by differential gene expression and alternative mRNA splicing during transcription. Few exceptions exist in this paradigm, the most prominent being that of B ant T cells, which are able to rearrange genomic DNA through somatic recombination and generate the huge variability of immunoglobulin and T cell receptor (TCR) repertoires.

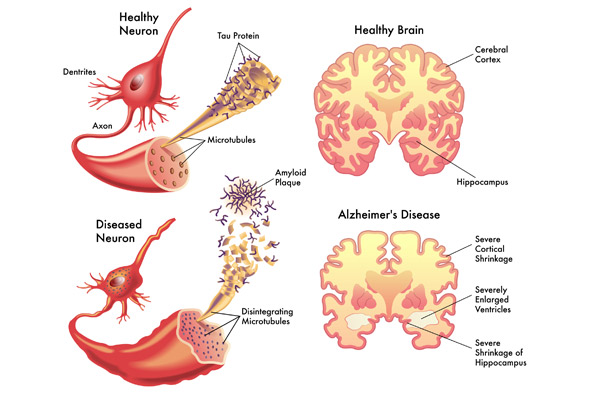

On the other hand, the brains of patients affected by neurodegenerative diseases often display mosaicism -the presence of mutations and different copies of certain genes in the tissue cells- which does not depend on mutations inherited by parents: for examples, the neurons of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) display more DNA and different copies of the amiloid precursor protein (APP) gene, which is one of the causes of this condition. Although this feature is common in neurodegenerative pathologies, its mechanism is basically unknown. In this sense, the paper published this week on Nature by Lee et al represents an important milestone of molecular biology and neuroscience: it provides a mechanistic base for neuronal mosaicism of patients with AD and other neurodegenerative conditions, proving that neuron can indeed perform somatic recombination (a feature that to date was thought to be exclusive of immune cells), while it also lays new ground to understand neurodegeneration.

Somatic APP recombination in AD patients neurons seems to rely on the activity of and endogenous reverse transcriptase that retro-transcribes variants of APP mRNAs into complementary DNA (gencDNA). GencDNA is then integrated into the genome and, during this process (although it’s not entirely clear) might suffer mutations that give birth to new genes that are, in time, expressed and translated into detrimental products. Since this fenomenon occurs simultaneously on multiple cells in the brain, the cortex of AD patients presents many neurons that harbour several different copies of the APP genes. AD might be more prone to spark in subjects in which the generation of APP gene pathogenetic variants is overabundant, but, interestingly, authors also reported that the amount of gencDNA variants correlates with age, which might account for the years required for the disease to manifest and for its age-related onset.

Source: Nature website, Science website, Nature Journal.